|

About a year ago Professor Debora M. Katz of Annapolis Physics

Dept. signed the guestbook, and after some e-mails I sent her

a 30W Shelby Bulb, the same vintage and make as our Centennial

Bulb. The reason was she has the facilities to test the bulb

in ways we could never attempt with big brother.

I put a few questions to her about filament size, (to dispell

the myth of it being pencil thickness), the actual heat by means

of a temperature coeeficient test, and an analysis of the 100

year old gases inside.

2008

Dr. Katz had this to say about the results;

"I

found the width of the filament. I compared it to the width of

a modern bulb's filament. It turns out that a modern bulb's filament

is a coil, of about 0.08 mm diameter, made up of a coiled wire

about 0.01 mm thick. I didn't know that until I looked under

a microscope. The width of the Shelby bulb's 100 year old filament

is about the same as the width of the coiled modern bulb's filament,

0.08 mm.

We didn’t want to break the Shelby

bulb so we used the laser."

For comparrison the thickness of a human hair is approximately

0.06-0.09 mm.

Below are some pictures of the experiment using the laser.

When asked if the thickness could attribute to the longevity

she replied,

"I don't have a clear answer.

I think the thickness may make a difference. I wonder if the

filament does not get as hot. I think I would like to see if

I can get the spectrum."

|

Thank you Professor Katz, for your time and skills

in answering our puzzling questions. We look forward to your

next tests!

(Please click thumbnails to enlarge) |

Nov. 2009

In 2010 Dr. Katz assigned a grad student, Ensign Justin Felgar,

to continue with the tests on a working 30W Useful Light bulb.

Here is Dr. Katz's explanations of the pictures;

1&2. Two multimeters. One for measuring current, the other

for voltage

3. Variac to control voltage to bulb.

4. Bulb in socket

5. Using an ommeter to measure resistance of the filament at

room temperature.

6 & 8. Showing the software used to measure bulb's spectrum

7. Close up showing sensor used to measure spectrum

9. Two multimeters. One for measuring current, the other for

voltage

10. Close up showing sensor used to measure spectrum

11&12.

Showing the bulb at 80V and 120V

Thank you Professor Katz, for your time and skills

in answering our puzzling questions. We look forward to your

next tests!

(Please click thumbnails to enlarge)

At the completion of these tests, and other research,

Ensign Justin Felgar wrote a great paper on Shelby bulbs. Please

follow this link to his published

paper, in pdf form. He did an amazing job. Fantastic! |

2011 Interview

|

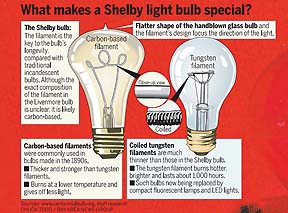

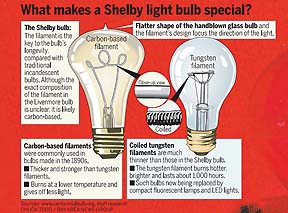

“It struck me as almost ridiculous that this 100-yearold

technology is still functioning. I thought for sure that all

the physics must have been worked out,” said Debora Katz,

a U.S. Naval Academy physics professor who first learned about

the bulb when it was featured on the “Mythbusters”

television show. Intrigued, she sent her students to dig up Chaillet’s

patent. Its contents were disappointing: Only the configuration

of the filament and the shape of the handblown glass he used

in an effort to reduce light refraction and better direct the

bulb’s light were described. Information that might have

shed light on his bulb’s life span, such as the

composition of its fi lament and the gas surrounding it, were

absent.

Livermore’s bulb can’t be tested directly for fear

of destroying it, Katz said. Still, experiments conducted on

identical Chaillet bulbs might

hold clues. To determine its thickness, Katz’s team shined

a laser on a Shelby filament and measured the pattern produced

on a screen behind

the bulb. The results showed Chaillet’s filament was eight

times thicker than that of a modern bulb. Another difference

is wattage. Modern household bulbs range from 40 to 200 watts

— the Centennial bulb

now gives off 4 watts, about as strong as a night light. Thought

to have been a 30-watt bulb when installed, the Livermore light

seems to have decreased in power over time.

“You can think of it as sort of an animal with a low metabolism.

It’s giving us less energy per time, so it can keep on going

longer,” Katz

said. Other data add credence to the reports that the Centennial

Light filament was carbon-based — the norm before tungsten

filaments were introduced in the early 1900s. The results are

documented

in “The Centennial Light Filament,” a 2010 paper by

one of Katz’s former students.

Author Justin Felgar found the hotter the Shelby got, the more

electricity got through it. The opposite is true for modern tungsten

filaments, suggesting the Shelby fi lament is made of something

else. To determine its makeup, Katz said she wants to rip apart

a Shelby bulb that isn’t functioning and run its filament

through the Naval Academy’s particle accelerator —

hopefully before the Centennial Light’s 110th birthday in

June. “Perhaps there’s just some fluke with that particular

(bulb),” Katz said, adding, “I think we should at least

be able to talk about what the

differences are between the Shelby bulb and the contemporary

bulb. Whether those differences account for longevity, I don’t

know.”

To see the full article go to Page1

or Page 7. |

|